WARNING: The subject of the following review contains references to gore, explicit violence, and horror themes. Reader discretion is advised.

Special thanks to Daulton Morrison for critical contributions to this post.

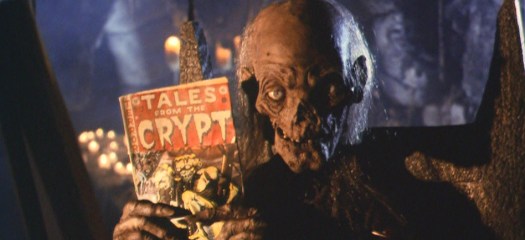

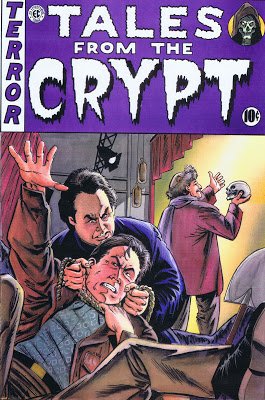

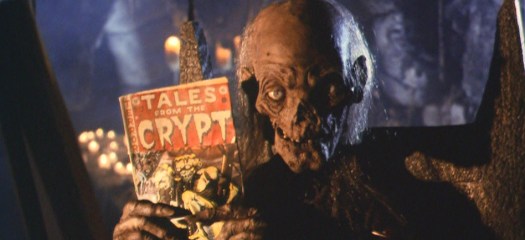

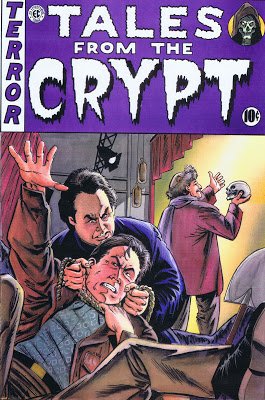

With October still in its early days, I figured I owed it to myself to get back into reviews by channeling some early Halloween spirit. Thankfully, I’ve got plenty in the way of material for that, because if there’s anything my now year-old review of “Creepshow” should prove, it’s that I adore horror anthologies, especially those that pay homage to the pulp horror comics of yore. Other than “Creepshow”, however, there’s only one extremely popular example of such tributes that continues to hold fondness and popularity among horror enthusiasts, and that example is the 1990’s TV show, “Tales From the Crypt”. Named after and based on stories from the horror comic magazine of the same name (along with stories from “Vault of Horror” and “Haunt of Fear”), the show garnered all sorts of attention on both sides of the critical spectrum for its campy sense of dark humor, wide variety of stories within episodes, and eclectic casts across the season. Its decrepit, pun-loving “Master of Scare-imonies”, the Crypt Keeper, has likewise become an icon among horror hosts, and even those unfamiliar with the show can at least point to him as a horror legend in his own right. In the first of a few Halloween-themed pieces between requested material, we’ll be taking a look at some of the most shocking, atmospheric, and darkly humorous of the show’s offerings across its seven seasons. With that in mind, I must once again bring up a content warning, as the episodes on this list can get REALLY disturbing. So I hope you all have strong stomachs, boils and ghouls, because here are Rich Reviews’ Top 10 “Tales From the Crypt”.

10. Split Personality

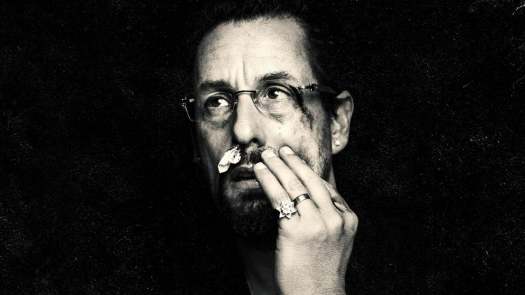

One of the most defining aspects of “Tales from the Crypt” is its sense of bitter, dark humor, and when it takes center stage in the more comedy-focused episodes, the results tend to be fairly… mixed, to say the least. The fan favorite “Cutting Cards”, for instance, fell just shy of taking this list’s 10th spot, for while that story of two bitter gambling rivals benefited from great performances, the end result fell fairly flat due to the one-joke narrative and the predictable twist. “Split Personality”, on the other hand, is an escalating shock comedy that benefits from all the things absent from that episode. It stars Joe Pesci as a two-bit conman who comes across a rich pair of twin sisters, opting to act as his own “twin” and court them both simultaneously to amass their immense fortunes.

What makes this episode work on the comedic side of things is the performance of Joe Pesci. It’s no secret that he’s perfectly at home playing a foul-mouthed, scheming con artist, but what’s especially remarkable is how well Pesci manages to pull of the lead’s facade of a humble gentleman, which makes the moments in which he breaks character all the more hilarious. On the more serious end of things, the narrative also manages to be suspenseful when it comes to the two sisters, for while it’s clear that they have their own tricks up their sleeves, it’s never too obvious what they have in store for the main character, making for something of a unique thriller amidst the shenanigans present in Pesci’s schemes. The episode looses points for leaning a bit too hard on the shock factor towards the end, but all in all, “Split Personality’s” performances and atmosphere make it a good episode to kick this list off.

9. The Reluctant Vampire

Yet another comedic installment in the series, “The Reluctant Vampire” was one that I was originally going to list as an honorable mention for being as cheesy as it is, but was ultimately swayed by another fan of the show to put it here on this list due to Malcolm McDowell’s spot-on performance as the title character. Said character, Donald Longtooth, is a meek nosferatu who works as the night shift security guard at a blood bank in order to peacefully satiate his thirst. He’s forced to feed off of criminals and ne’er-do-wells to do so, however, when Mr. Crosswhite (George Wendt), threatens to lay off employees due to the subsequent blood shortage.

The tone of this episode is distinctly goofy and satirical, what with the hammy performances across the cast and the bumbling characters, most notably this story’s incompetent Van Helsing as portrayed by the normally terrifying Michael Berryman. Over the top as the final scenes become, however, this episode is legitimately funny and even heartwarming in some places, and both can be traced back to Malcolm McDowell’s acting. Never one to give a half-hearted effort no matter what the material may be, McDowell is great at playing up the meek and eccentric aspects of Longtooth’s character, and his chemistry with the female bank teller is all the more endearing and adorable because of it. One could argue that this fluffier episode even adds some variety to the series as a whole, and viewers looking for a more optimistic story to see on Halloween should definitely check this one out, especially seeing as how most episodes tend to be as dark as the following…

8. Easel Kill Ya

Far on the other end of the spectrum is a twisted and bleak psychological thriller episode from the show’s third season. The title is about the only instance of camp in this story, following alcoholic painter Jack Craig (Tim Roth), whose macabre depictions of death in his art catch the eye of a mysterious benefactor who offers generous sums in exchange for more art in this style. This style, however, is a truly sick and costly one, as it entails Craig murdering random bystanders and using their blood as paint for the canvas, and even the support and love of his girlfriend Sharon seems unable to disperse the darkness within.

This episode’s twist becomes a fairly predictable one the further along the story goes, but what makes “Easel Kill Ya” work so well is its commitment to tone and intensity. The cinematography and sense for scene composition, for instance, is arguably the darkest and gloomiest of any episode of the series, and it’s all in service to a dark character piece about how addictions can take on many dangerous forms. The star of this nasty morality tale, the ever-underrated Tim Roth, does wonders bolstering the already disturbing story, delivering a tortured and temperamental performance befitting a violent recovering addict past his artistic prime. It’s episodes like this one that remind viewers that “Tales From the Crypt” was just as capable of legitimate and visceral horror when it wanted to deliver. Still, while there’s certainly more of that to come, the show was never one to forget how to have fun with horror. Case in point…

7. The Ventriloquist’s Dummy

One could probably guess which direction “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy” leans in, what with Bobcat Goldthwait and Don Rickles as the stars of this episode. Still, props should be given to this one for having a little bit of everything that makes “Tales From the Crypt” so memorable. Its story follows Goldthwait as Billy Goldman, an amateur aspiring ventriloquist seeking advice from his childhood hero, Mr. Ingles. This veteran entertainer, played chillingly by Don Rickles, had disappeared from the industry after a mysterious incident, and to Goldman’s terror, he’s soon to find out the ghastly secret behind his career.

Up until the second half, this episode is mainly driven by the performances and chemistry between the leads, and the interplay between Bobcat Goldthwait and Don Rickles is phenomenal. Goldthwait is surprisingly capable in the role of the naive upstart, and the normal bombastic and crass Don Rickles deserves special mention for how initially nuanced, bitter, and imposing his character is. What would have otherwise been a slow boil until the reveal is turned into a character study about the dynamic of new talents and their inspirations, and Goldman’s over-eagerness to follow Ingles’ path to the letter leads him into a deadly struggle reminiscent of an early Sam Raimi horror-comedy. I won’t spoil the circumstances of the hard turn into gory slapstick, but I will say that it’s made much less standard and predictable by the loud, over-the-top comedy styles of its actors. Crazy and absurd as it is, this one will shock and delight in equal measure, and is perfect for fans of more satirical horror.

6. None but the Lonely Heart

Coming back to the straight-up terrifying end of things, we have a darkly suspenseful and shocking season four opener about a charming, yet devious conman (Treat Williams) who seduces wealthy old women into marrying him, all so that he can kill them and pilfer their considerable fortunes. The latest in his line of prey is widow Effie Gluckman (Frances Sternhagen), whose initial skepticism is soon culled by Howard’s humble facade. Smoothly as his scheme seems to be running, however, there’s someone or something fully aware of the mountain of corpses Howard has accumulated, and it soon becomes apparent that even the most devilish of charmers can’t run from their sins forever.

This episode of “Tales from the Crypt” actually served as the directorial debut of actor Tom Hanks, which is especially remarkable considering how on-point the cinematography of this one is. Hanks and the rest of the episode’s crew make great use of darkly-lit suspense and gore shots, and the true terror of the widows’ predicaments are expertly conveyed with the utilization of sickening reaction shots and keenly-executed perspective. Removing that, however, this one is still a great karmic horror story, with Treat Williams delivering a contemptible character in Howard Price. His shameless characterization, highlighted in a scene where he claims he is doing each widow a favor before their deaths, makes the inevitable fate of Effie all the more tragic and gut-wrenching, as does Frances Sterhagen’s turn as the heartbroken and vulnerable old woman. Also, despite taking an abruptly supernatural turn, the twist ending of this episode provides a textbook case of the series’s brand of poetic justice, and chances are good that you’ll be cheering for the karma on display… if you’re not wincing at how gory the end result is. And speaking of gory twists…

5. Top Billing

Less a straight-up horror at first glance and more a psychologically driven cautionary tale on the dangers of career entitlement, this episode, “Top Billing” deserves special mention for being yet another example of a normally comedic actor displaying some surprising dramatic chops as the star of a character study. The normally comical Jon Lovitz plays Barry Blye, a struggling actor in competition with a cocky commercial star (Bruce Boxleitner) for the lead role in a local theater’s production of “Hamlet”. Desperate for his big break and knowing his rival is likely to make a big role, Barry resorts to drastic extremes in order to keep him out of the cast and secure his own career, only to find out there’s more risk involved in auditioning than he could have ever imagined.

This excellent season three entry doesn’t start becoming a straight horror/thriller until the second half, but its narrative works in the same way most of the best episodes of “Tales From the Crypt” do- its commitment to dramatic tension. Adding onto that heavier emphasis on personal drama is the on-point acting of Jon Lovitz, whose portrayal of Barry’s struggles and desperation will illicit natural sympathy from audiences, at least until he starts dipping to extreme lows. Bruce Boxleitner also deserves some credit as the commercial actor, Winton Robbins, for perfectly embodying the superficial charm of cocky up-and-comers of this nature, as does John Astin as the theater director, who is laughably entertaining as a gloriously hammy auteur drunk on his own pretentiousness. Still, while the episode’s story is more than content in satirizing the acting industry, the horror end of things really settles in when Barry becomes willing to do anything (i.e. murder) to further his career, and his final fate upon securing literally deadly role sends a haunting message about how entitlement can corrupt even the most earnest and dedicated of people in their craft. As one with personal aspirations of breaking into the entertainment industry on various levels, this one personally hit close to the vest for me, and if this were a purely personal list of episodes, “Top Billing” would easily land somewhere in the top three. Still, if I may, I’d like to bring us back to the topic of suspense and atmosphere…

4. The New Arrival

This one is EASILY my personal favorite among the episodes of the fourth season, an already-excellent chapter in “Tales From the Crypt” containing classic episodes like “Split Second”, “None But the Lonely Heart”, “Easel Kill Ya”, and “Top Billing”. While those episodes touched upon rather specific brands of horror, however, “The New Arrival” earns extra points for evoking the kind of eerie, unsettling suspense that will shake all but the most hardened of horror enthusiasts. It tells the story of Dr. Alan Goetz (David Warner), a snobby radio psychologist at risk of loosing his time slot on the airwaves to a popular shock jock. To prevent this, he agrees to a live recorded session with the daughter of the show’s most frequent caller (played by Poltergeist actress Zelda Rubenstein) at her home. What starts out as a surefire way to save the show, however, turns into a twisted trap inside a decrepit old house occupied by the eccentric mother and the ghastly cries of a daughter that remains yet unseen…

The setup of this one is typical of “Tales From the Crypt”, as Dr. Goetz is exactly the kind of smarmy know-it-all in need of karmic education (especially considering his neglectful, pseudo-psychological approach to his field), and David Warner gives an appropriately dour performance. What makes “The New Arrival” stand out, however, is the suspense it builds up through atmosphere and surreal horror. The house is an old fashioned, chewing gum-covered husk of a home that wouldn’t be out of place in an early Tim Burton film, and its inhabitant, Felicity’s mother, is a polite, hospitable, yet clearly disturbed old woman made all the more unnerving by Zelda Rubinstein’s perfect portrayal. From the get-go, it’s clear that her brand of parenting is directly responsible for Felicity’s psychotic, borderline bestial behavior, but every second on screen becomes a testament to her underlying craziness thanks to the nuance of Rubenstein’s acting. That buildup, however, should not imply the inevitable twist goes in any predictable direction, and “The New Arrival’s” payoff to that warped buildup makes it a definite classic. Which is saying something, considering the next entry…

3. Yellow

The only thing keeping “Yellow” from the top spot is its deviation from typical horror and the element of personal judgment. Otherwise, this one’s a perfectly executed war-themed episode that deserves credit for its sheer ambition and production value, as it’s the only episode of “Tales From the Crypt” to be an hour-long special. This grand finale to the show’s third season is a more grounded war story about Lieutenant Martin Kalthrob (Eric Douglas), who pleads his father, General Kalthrob (Kirk Douglas) to grant him a discharge. Being a hardened man of war, the General refuses but promises him a transfer upon the completion of a special mission. When that mission comes about, however, Martin abandons his posts and comrades, dooming him to the designation of being “Yellow” and worthy of a court marshal and firing squad execution.

As mentioned before, the production values and gritty direction of Robert Zemeckis deserve special mention for how bold a turn they allowed the series to take for this one episode. If the time frame weren’t as constricted as it was, one could very well have seen potential in “Yellow” as a feature-length film. Beyond that, however, this episode should be lauded for its commitment to a more visceral and grounded type of horror beyond that of the monsters so common throughout the shows run: the Hell that is war. Punctuating this is magnificent character chemistry between father and son, as the legendary Kirk Douglas does wonders at conveying his inner conflict beneath the facade of a poor man’s Patton while Eric Douglas gives a pitiable performance that, along with the circumstances of his enlisting, makes his subsequent cowardice all the more understandable. “Yellow” isn’t just a good episode of “Tales From the Crypt”, it’s transcendent, and while I have more personal picks for episodes more emblematic of the show as a whole, it’d be entirely dishonest not to include it on this list.

2. Confession

“Tales From the Crypt’s” seventh and final season was a drab, boring slog of a finale to a show all about the sheer entertainment of horror stories. To that end, I was hesitant to check this one out in spite of trusting the recommendation of that fan of “The Reluctant Vampire”. He told me to expect a great execution of the crime thriller genre with a standout performance from Eddie Izzard. What I couldn’t have possibly expected was one of the best utilizations of the show’s established formula. The story in question? A grisly, camp-free murder mystery in which a seasoned serial killer analyst and interrogator (Ciaran Hinds) is pitted against a pompous horror film writer (Eddie Izzard) accused of the decapitations of several women. With the interrogator surrounded on all sides by uninterested police officers and a suspect that refuses legal counsel, this mystery is sure to be one in which the answer is unknown to only himself… for better or worse.

There’s a lot about “Confession” to love, from its utilization of self referential horror tropes without resorting to comedic deprecation to its sense of characterization, especially in regards to its two leads. Pride is a cardinal sin among both interrogator and suspect in this scenario, with Ciaran Hinds’s weathered and cool demeanor offsetting Eddie Izzard’s brilliantly disturbed, temperamental and egotistical performance. While investigator Jack Lynch is prideful in the sense that he’s sure he’s seen every killer, Eddie Izzard’s Evans is so confident in his “knowledge” of killer cliches that he’s counting on that as the “smoking gun” of his innocence. The true culprit is one I won’t spoil, but “Confession” should still be praised for having that rare brand of twist ending that works even better upon repeated viewings, as well as for the aforementioned mastery of tone and character voice. So, what could possibly have topped this tangled web of horrific intrigue?

1. Carrion Death

“Carrion Death” is the kind of horror story that’s so simple, it defaults into nightmarish perfection. It’s not necessarily the best written, or the scariest, or even the best one direction-wise, but its execution of a practically pedestrian narrative is made legendary by everything great about “Tales From the Crypt”- dark, poetic, justice, an almost laughably despicable lead, and the kind of direction and framing that’s evocative of an inescapable nightmare. It stars Kyle MacLachlan as Earl Raymond Diggs, an unapologetic serial killer on a dogged path towards the Mexican border with the law hot on his trail. Good news? His pursuer, a lone police officer, is dead by his hands. Bad news? He’s handcuffed to the cop and forced to walk the harsh desert with disaster after disaster crossing his path, all while a mysterious and clearly famished vulture awaits the moment that the inevitable cannot be delayed any further.

Silly as this episode can be (the tenacity of that vulture requires a lot of disbelief to be suspended), this episode’s approach to its admittedly bare-bones narrative makes it the perfect kind of episode to start a binge of horror this Halloween season. As it unfolds, it becomes less a story of a killer on the run from the law and more a fable about one sinner’s futile attempts to run from death itself. That’s all I’ll say, since I desperately want you all to check this and the rest of the series out, but I’m confident I did well to kick off the season. Drink deeply, readers…

October is here.